Tales of the Magic Skagit: Bruce McCormick and the Monster Book of Pioneers

“Every community writes its own history just as surely as every community makes its own history.“

— Preface from An Illustrated History of Skagit and Snohomish Counties (1906)

“The best heritage the pioneer can leave to future generations is the simple yet powerful story of his life–of hardships endured, of dangers faced, and his final victory over wilderness and desert plain.”

— Theodore Roosevelt

Fans of the Harry Potter series may recall that as the boy wizard was to begin his third year at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, one of his required textbooks was “The Monster Book of Monsters” — an aptly named work that was not only a vast compendium of monsters inhabiting the wizarding world, but was itself a monster. In order to safely read the book, students had to first subdue it by gently stroking its spine or else risk mutilation. I must admit that such bits of whimsy are no small reason that I avidly consumed all seven Harry Potter books, and why my grandsons have read or listened to them more times than I can count.

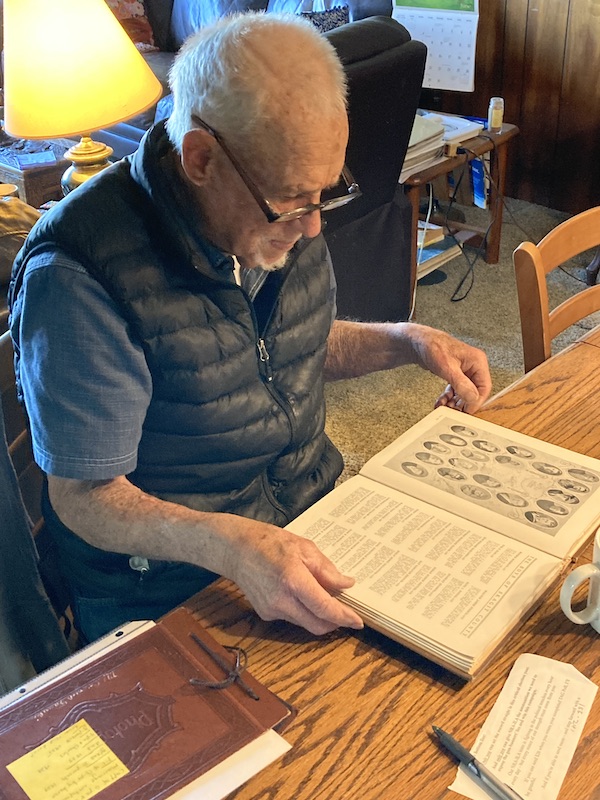

I was reminded of “The Monster Book of Monsters” when I first beheld a book belonging to Bruce McCormick, who had inherited the tome from his father, who had in turn inherited it from Bruce’s grandfather, and early Skagit Valley (white) settler, David L. McCormick. It’s an imposing work of tooled leather and gilded lettering, easily rivaling the New York City phonebook from back in the days when printed urban directories served as booster seats for many a toddler at the kitchen table.

With its gold embossed title, “History of Skagit and Snohomish Counties, Washington,” and bearing the official seal of the State of Washington (complete with the profile of the Father of Our Country), the book is itself a pioneer — a leather-bound time capsule that yields a sweeping profile of life in the Magic Skagit at the turn of the 20th century.

The first page of McCormick’s heirloom book immediately establishes its bona fides as a portal to the Skagit Valley’s pioneer past, reading as follows:

AN ILLUSTRATED HISTORY

OF

SKAGIT AND SNOHOMISH

COUNTIES

THEIR PEOPLE.

THEIR COMMERCE AND THEIR

RESOURCES

WITH AN OUTLINE OF THE EARLY HISTORY

OF THE

STATE OF WASHINGTON

ENDORSED AS AUTHENTIC BY LOCAL COMMITTEES OF PIONEERS

INTERSTATE PUBLISHING COMPANY

1906

The book’s dedication reads, “To the pioneers of Skagit and Snohomish Counties Washington, those who have gone and those who remain. This work is dedicated as a token of appreciation of their virtues and their sacrifices.” This lofty sentiment is followed by the quote from Teddy Roosevelt that I cited at the outset of this story.

The table of contents that follows quickly reveals why “The Monster Book of Pioneers” is as large as a Victorian family bible. Part I of the book is devoted to Washington history, and is divided into the following chapters:

Chapter I: Explorations by Water

Chapter II: Explorations by Land

Chapter III: The Astor Expedition

Chapter IV: The Northwest and Hudson’s Bay Companies

Chapter V: Period of Settlement

Chapter VI: The Oregon Controversy’

Chapter VII: The Cayuse War

Chapter VII: Early Days in Washington

Chapter IX: The Yakima War

Part II of the book is devoted to Skagit County history in eight chapters: five of which detail periods of time from first settlement through 1905, and three of which cover the political organization of the county, along with detailed histories of the cities and towns comprising it. There are places included that I’d never even heard of (do Montborne, Sterling, Thorne, and Ehrlichs ring a bell, anyone?).

A large portion of the book is dedicated to biographical sketches of the earliest white settlers of the Skagit Valley, and its index lists them alphabetically from Linus Abbot of Mount Vernon (page 751) to James M. Young of Sedro-Woolley (page 708). Included as well are portraits of a number of these pioneer notables, many of whom were living at the time of the book’s publication.

As you might imagine, my friend Bruce treasures this book of Skagit Valley pioneer history — not only for its insights into its past, but as a keepsake that has been a part of his family for 116 years (Bruce turns 92 next month, by the way). In fact, the first thing you see upon opening the “Illustrated History” is the penciled inscription atop an otherwise blank page, “Property of D. L. McCormick/G. D. McCormick” — Bruce’s grandfather David and his grandfather’s identical twin, George. To give you an idea of the narratives the book contains, I offer this verbatim account of Bruce’s granddad, who Bruce proudly recalls as a stern man who regarded his grandson with some suspicion (which reveals more about Bruce than it does his grandfather…but that’s another story).

DAVID L. McCORMICK is one of the pioneer farmers of the La Conner section of Skagit county,

having first located there in the early seventies. He comes of a family which was well known in the early days of Hocking Valley, Ohio. His father, William McCormick, a Pennsylvania farmer, went to Ohio before railroads had opened up that country, took up government land there and farmed it until his death shortly before the Civil war. Mrs. Elizabeth (Johnson) McCormick, mother of our subject, was born in West Virginia, but her parents moved to Ohio by ox team when she was a small child, and she lived there to the ripe old age of ninety-four years. David McCormick was born in Perry County, Ohio, in 1850, and received his school training in that state. He remained on the home place until he reached the age of nineteen, when he went to live with an uncle in Iowa, and four years later he started for Washington. The trip by rail to San Francisco occupied two weeks. After five days at the Golden Gate he took passage for Victoria, Vancouver Island, and from there went to Seattle. In company with five others he purchased a row boat and rowed it to La Conner, where he met Nelson Chilberg, an old friend from Iowa. With him he went up the Nooksack river and located a claim, which, however, he never carried to patent. During the following fall, having returned to La Conner, he took a pre-emption claim four miles north of the city, and upon this he lived at intervals until 1877, when he bought his present place of one hundred and twenty acres northeast of La Conner, paying $10 an acre for the cleared land. Later he sold his pre-emption land.

In 1889 Mr. McCormick returned to Ohio, and there, in June, married Miss Margaret Case, daughter of Honorable Oakley Case, one of the well-known citizens of Hocking county. Mr. Case was at one time editor of the Hocking Sentinel. He was elected probate judge of Hocking county in 1860, and served two terms in that capacity, afterwards becoming mayor of the town in Logan. For a term of years he was an influential member of the Ohio legislature; he also served as chief clerk under Secretary of State William Bell, Jr., in 1876 and 1877. Mrs. Margaret (James) Case, mother of Mrs. McCormick, was a Virginian by birth, but was taken by her parents when a child to the famous Buckeye state. Mrs. McCormick was born in Logan, Ohio, in 1857, and received her education in the schools of that city, graduating from its High school. For six years she served as toll collector on the Hocking Valley canal. Six children have been born to Mr. and Mrs. McCormick, all during their residence in Skagit County, namely, William F., in 1892, David O., in 1894; Margaret E., in 1895; George D. And Charles A. (twins), in 1898, and Helen E., in 1900. Mr. McCormick is a member of the Order of Eastern Star. Inheriting the qualities which made his forefathers forceful in the pioneer days of Pennsylvania, Mr. McCormick has proven himself one of the sturdy and substantial men of Skagit County. Though thoroughly public spirited, he has manifested no special ambition for leadership or political preferment, but has been content with membership in the producing class, the men who, without ostentation, go to work with energy and accomplish something, the men who form the real strength of any community. That he has been an active, earnest worker is evinced by the fact that two hundred acres of his fine farm land have been well cleared and brought to a high state of cultivation. He has also gathered around his home the comforts and conveniences which add so greatly to the pleasures of rural life. It is no longer necessary to bring water for house use in a wheel-barrow, as it was when he began the struggle with pioneer conditions, any more than it is now necessary to navigate the sound in a row boat. With plenty of cattle, horses and other livestock, sufficient farm machinery and an abundance of fertile land, he is now in a position to carry on his agricultural operations with satisfaction and profit.

There are a number of things that stand out for me in David McCormick’s bio as I parse their meanings in the context of their time. The first, and one that typically resonates through “tales of the pioneers,” is the outright pluck and audacity of their characters. But let’s dwell a bit on the period of David L. McCormick’s birth. Looking backward, it had been less than three-quarters of a century since the United States declared its independence from Great Britain. Looking forward, David McCormick would be 11 years old at the outbreak of the Civil War — which means that Bruce McCormick, a man alive in the 21st century, was able to converse with one who would have had a living memory of the War to Save the Union. A scant eight years later, with the Union strained but intact, David McCormick would leave home to begin his journey West.

Which brings me to a second thing that stands out in the story of a life in two (albeit, very long) paragraphs. David McCormick was very much a man caught up in an American migratory journey that began with his father, who immigrated from one of the original thirteen colonies to the frontier of Ohio, and “opened up that country” in the days before rail travel. By contrast, his son, at the tender age of 22, would spend two weeks riding the rails in his journey to San Francisco, covering a distance that less than seventy years earlier would probably have taken the Corps of Discovery a year to traverse.

Another very telling part of David McCormick’s bio is his choice of a life partner. Many of the men who journeyed west in the mid-19th century took wives from among the First Peoples who became their neighbors. In her history of Fidalgo Island, First Views: An Early History of Skagit County: 1850 – 1899, local author and historian Theresa L. Trebon writes, “By 1870, all of Fidalgo’s first white settlers, and most newcomers, had taken Indian women as their partners: eight had started families. The relationships were common throughout Whatcom County, Whidbey Island, and the San Juans. An 1891 Anacortes American article, for example, noted that of the seventeen men to first settle along the Skagit River, sixteen had taken Indian women as wives. In some instances, these unions helped bridge cultural differences between the Indian and white communities, enabling two very different worlds to merge and coexist. But in other situations the outcome was different. As greater numbers of white women began arriving in Washington, white men frequently cast their Indian partners aside, oftentimes retaining custody of the children they’d had together. Rarely was the Indian mother allowed further contact with her children, or her fate noted in family or community histories. But many of the white-Indian relationships recorded in Fidalgo’s 1870 census would prove exceptional in their longevity.”

As it turned out, David McCormick chose neither of the above matrimonial options, preferring instead to return return east for a bride. It’s obvious from his choice that he set a high standard on accomplishment. Margaret Case was not only from a notable Ohio family, but she was a high school graduate with some job experience (her toll collecting gig on the Hocking Valley canal). One can assume that whatever trepidation the young woman from Logan, Ohio might have had about heading “way out west,” she could at least take comfort in being the wife of a successful farmer, living in a place that was already enjoying the “comforts and conveniences which add so greatly to the pleasures of rural life.” By the time Margaret’s last child was born, the West had effectively been “won” — which makes An Illustrated History of Skagit and Snohomish Counties as much a victory lap as a work of history.

Which brings me to a final takeaway from the story of David L. McCormick as viewed from the beginning of the 20th century. The fact that McCormick enjoyed an “abundance of land” upon which he was able to “carry on his agricultural operations with satisfaction and profit” was the result of a zero sum game played out in the wake of the 1855 Treaty of Port Elliott. McCormick’s bio in the Illustrated History of Skagit and Snohomish Counties notes that in 1877, “he bought his present place of one hundred and twenty acres northeast of La Conner, paying $10 an acre for the cleared land.” By way of historical context, one of the informational displays at Swedebs Park, across from La Conner in Swinomish Nation, points out that “In 1863, settlers’ claims were staked at March Point at the northern end of the Swinomish Reservation, despite complaints (by the Swinomish) to the government. In 1873, President Ulysses S. Grant simply removed March Point from the Reservation territory. By 1879, just 24 years after Treaty Time, over 10,000 acres had been diked for conversion to agricultural lands, a process that accelerated through the 1900s.”

I’ve set out in this Tales of the Magic Skagit story to introduce our audience to the historical resource that is also the treasured family keepsake of a living link to Skagit Valley’s pioneer past, in all its inspiring and problematic glory. I have previously recorded a Tales of the Magic Skagit podcast with Bruce about his book and his grandfather, and my intention is to revisit both the book and Bruce for stories about other pioneer families of the Magic Skagit. Most likely our next one will be about John Peth, who recently figured in a Tales of the Magic Skagit story about the town of Edison and a failed utopian community known as Equality Colony. Bruce remembers John Peth as well.

I should also mention that our latest podcast series, Beaver Tales, will recount stories about the people who were here — and who remain here — when David L. McCormick and John Peth first arrived. If all we know of the history of this place is what transpired from the mid-19th century on, we don’t really know the history of this place. Fortunately, in the case of the “Monster Book of Monsters,” the period of westward migration to the Skagit Valley is well documented in a book now in the possession of David McCormick’s last remaining grandson, and I look forward to bringing our Tales of the Magic Skagit readers more of its stories, along with color commentary from a living link to our pioneer past.

If you happen to hold to the aphorism that “the apple never falls far from the tree,” then I should close with an observation about Bruce McCormick that reminds me of a tribute paid to his grandfather. Like his grandfather, I think one can safely say that Bruce, “has been content with membership in the working class, the men who, without ostentation, go to work with energy and accomplish something, the men who form the real strength of any community.” May we all, men and women, native and newcomer alike, live up to that same accolade.

You can read my original story about Bruce McCormick, “The Life and Times of Honker McCormick,” by clicking here. You can listen to a Tales of the Magic Skagit podcast interview with Bruce by clicking here.