Tales From the Magic Skagit: The Life and Times of “Honker” McCormick

It may surprise you to know that I’m not one for hyperbole. The way I look at it, the constant use of superlatives when applied to the patently mundane merely cheapens the sentiment when you come across the real deal. The fact that I tend to speak of the Skagit Valley and its people, places, and history in glowing terms is because — let’s be honest — we live in a superlative place.

Which is why when I call Bruce McCormick a “living legend,” I mean it quite literally. If the cap fits, wear it — even if the cap says “Honker.” Stay with me here, and I’ll explain.

Bruce McCormick turned 90 last December. By any measure, nine decades is an impressive run — particularly when you are still spry enough to incubate waterfowl eggs, tend to nesting boxes, maintain an aquatic avian refuge, organize binders full of newspaper clippings of life in the Skagit Valley, collect shotgun shells and baseball caps, catalog and display wildfowl art in various media, and occasionally entertain guests with a rendition of Woody Guthrie’s “Roll On Columbia” on a well worn six string. It takes more than a few decades to incorporate that many proclivities into a single unique carbon-based entity. At best, a half century would constitute a good start. At 90, however, you’re pretty much cruising in overdrive. And in Bruce’s case, you’d be whistling “Peggy Sue” with the top down in your ’47 Chevy and the wind in your hair —or what’s left of it.

Greater than the sum of his obsessions, however, Bruce McCormick is a living link to the Skagit Valley’s pioneer past — a first hand witness to a bygone era of immigrant settlement. For Bruce, that past is more than a collection of newspaper clippings or museum artifacts — it is remembered oral history learned at the knee of his grandfather, David McCormick. They’ll be more to say about David McCormick…but first, l’d like you to meet his grandson.

Walk into the McLean Road home Bruce shares with his partner, Sally Rode (who comes into the relationship with her own set of pioneer bona fides), near the La Conner Whitney Road intersection. It has been Bruce’s home for seven decades, and from his front yard he can see La Conner in the distance, visible across acres of farm land along with the ghosts of ancestors whose photos are painstakingly preserved in album collections that Bruce is willing to share with me.

My first reaction upon setting foot in Bruce and Sally’s home was that I had wandered into a wing of the National Audubon Society. Virtually every square centimeter of wall space is covered with paintings and prints of primarily water fowl, while shelving and other available horizontal surfaces are chock-a-block with decoys and the occasional bit of taxidermy. One is immediately sensible of an abiding passion of Bruce McCormick’s. How else do you explain the fact that during his life he has had both hunting and game farm licenses? Bruce has loved raising and hunting geese and ducks since he was old enough to remember. He recounts the story of how he got his first duck as a child as though it was yesterday, and it still puts a smile on his face, as well as on that of the listener. Bruce is one of those people whose sheer delight in his pastimes is infectious.

Bruce McCormick was born on December 5, 1930 at Raleigh Hospital in Mount Vernon (now the site of the Raleigh Apartments). His grandfather, David McCormick, was born in Perry County, Ohio, and came to Washington at the age of 23 after spending four years with an uncle in Iowa. His journey out west was a less arduous one than those experienced by previous westward immigrants some two decades earlier, but it was no light undertaking just the same: a two week trip by rail to San Francisco, followed by a passage to Victoria and Vancouver Island, and from there on to Seattle. In the company of five other intrepid souls, David McCormick purchased a row boat in which they rowed to La Conner. It was here that he met an old friend from Iowa, Nelson Chilberg, in whose company he traveled up the Nooksack River and located a claim. He soon returned to La Conner and took a claim on property four miles north of the city.

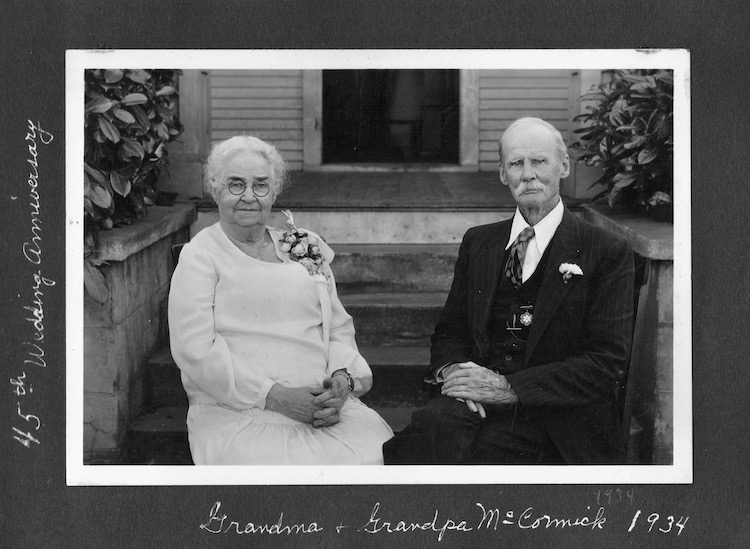

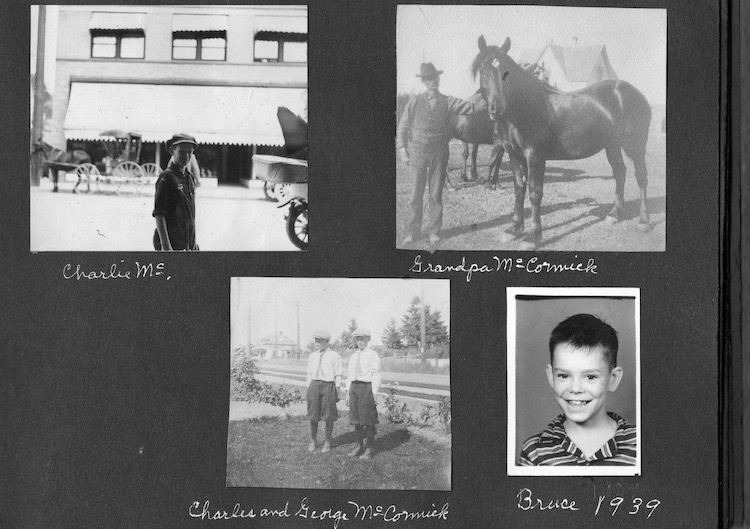

In 1877, David McCormick purchased 120 acres of cleared land northeast of La Conner for $10 an acre. Twelve years later he returned to Ohio and married Margaret Case, the daughter of a well-regarded family in Hocking County, and brought her back to the Skagit Valley. They raised six children, including Bruce’s father George and his father’s twin brother Charles, who were born on November 7, 1898.

The site of Bruce’s first home can still be seen off La Conner Whitney Road, just southwest of the intersection with McLean. “It’s the first place on the right, and it now belongs to Roger Burns,” says Bruce. “He has a beautiful little farm there, although I think he spends a lot of time at the naval base on Whidbey Island.” Bruce attended La Conner grade school when it first opened in 1937 — at which point he was already nearly seven years old. His high school graduating class consisted of seven boys and three girls, and as far as Bruce knows he is the only surviving male in the La Conner High Class of ’49. “I wouldn’t brag about my accomplishments as a student,” he says with a wry grin. “I think the principal was glad to get rid of me.”

Thanks to his father George’s purchase of a cow for $87 at a livestock auction, Bruce’s first occupation was dairy farmer. “We didn’t know anything about the cow’s history, but just a couple of weeks after my dad brought her home she had a heifer calf, which my dad gave to me. I named her Patsy. She had a heifer calf of her own that I named Pansy. I just kept changing one or two letters in the calves names as they were born so they’d be easy to remember.”

In 1944, Bruce got his first milk payment from Dairy Gold. It was a check for $12. Each month, he would turn his dairy earnings over to his mother, who would put them into a savings account. Every Friday, his mother would give him $5 that he could spend on hamburgers and movies. “I would either go to the Lincoln or the Lyric. There was also the Mission on the revetment, but we seldom went to that theater. The Lyric is now the Lido, across the street from the Mount Vernon Cafe. Movies cost ten cents.”

The dairy business was good for a young Bruce McCormick. “I bought my first car in 1947 — a four door Chevrolet. I bought it from Chuck Belgard, who went on to become the Mount Vernon police chief. My dad was not a Ford man, so we had to get on a list at Blade Chevrolet. It was right after the war and cars were hard to get, which is why he was on a list. It turned out that they had my dad on the list for convertibles. The car cost $2,250. I was a junior in high school with a brand new car. I think I even scared myself!”

Bruce eventually got tired of dairy farming. I don’t think it would be a spoiler alert if I told you that he’s the sort of person who would deal much better with adversity than with monotony. In any event, he took up truck driving for Puget Sound Freight Lines, traveling mostly between Seattle, the Skagit Valley, and Bellingham. “I was making pretty good money and I had sold the cows. Sometimes I had to make two trips in one day to Seattle, but the traffic wasn’t like it is today. I hauled a lot of beer.”

In 1951, Bruce’s father purchased the home on McLean Road where Bruce has lived ever since. “I never thought my dad would sell the farm, but he did, and he bought this house and the acre of land that it’s on for $8,000. Our first address was Route 1, Mount Vernon. Later it was changed to Route 1, Box 319. I still don’t know how they came up with that. Quite a few years later it became 1123 McLean Road, and finally 13251 McLean — my fourth address for the same place.”

Somewhere in between dairy farming and trucking, Bruce became an avid wildfowl enthusiast. “In 1977 I bought my first pair of wild birds,” he recalls. I’d had tame ducks and geese around here since I was a kid, but I got interested in the wild ones and I read up on them. I bought some Canada Goose goslings from a game farm and I just got to bragging about my ‘baby honkers’ so much — and people got so damned tired of hearing about them — that they pinned the nickname ‘Honker’ on me.”

So now you know.

Bruce has collected wildfowl in the form of prints, paintings, sculptures, stamps, story clippings, decoys, and various other collectibles. An out building just off Bruce and Sally’s back deck houses an incubator that not only keeps the eggs Bruce is hatching at a required temperature but also automatically turns them. Small enclosures opposite the incubator are for hatchlings who will eventually be sold or transitioned to a fenced pond where a variety of domestic and transient waterfowl swim, preen, and nap in the shade of the foliage.

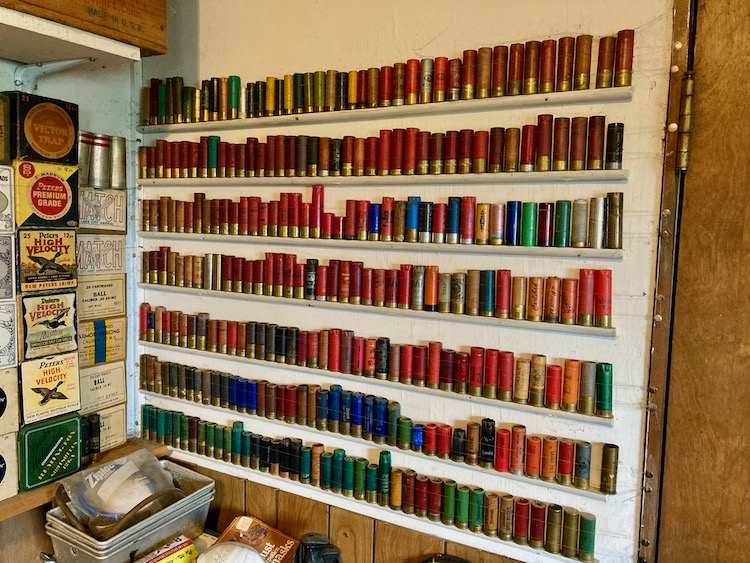

Ancillary to hunting waterfowl, Bruce’s incubator/baby chick greenhouse contains another of his collectible fetishes: shotgun shells. Seriously, we’re talking “Guiness Book of World Records” stuff here. In fact, Bruce can identify a spent shotgun shell cartridge faster than Sherlock Holmes can read the events of the past 12 hours of a person’s life in their collar lint. If there is a market for spent shotgun shells, Bruce McCormick has pretty much cornered it…and his incubator shed is a virtual Fort Knox of spent cartridge gold.

There is another collectible mania that is harder to explain, but is guaranteed to take your breath away in its audacious randomness: baseball/trucker hats. In a couple of barn-like storage and shop spaces on Bruce and Sally’s property, hats completely cover the walls and ceiling. Bruce can actually give you an exact count, which happens to be just shy of 6,000. He keeps a sharp eye out for duplicates, which aren’t allowed in the official tally.

But there is something that Bruce also diligently and lovingly collects that I especially appreciate: history. Much of that history is personal, and Bruce’s incredible grasp of details (do keep in mind that the man will be 91 this December) give his recollections a lyrical quality that play like an old time ballad. Listen to Bruce, and you’re getting up with him at 3:30 in the morning to take on a load of beer kegs in Seattle and then returning to Mount Vernon in time for breakfast at the Mount Vernon Cafe before walking the two blocks back in your rig and pulling up to your destination at 8am sharp. You can smell the coffee and feel the early morning sun on your face, as well as the satisfaction of a good day’s work done before noon.

Personal memories of a vanishing Skagit Valley pour out of Bruce’s office. Bookcases contain rows of white three-ring binders standing at attention and filled with story clippings tucked carefully into plastic sleeves that tell of life and events going back decades — right on up to a recent Skagit Valley Herald story about me. Which means I have become an official piece of Skagit Valley history!

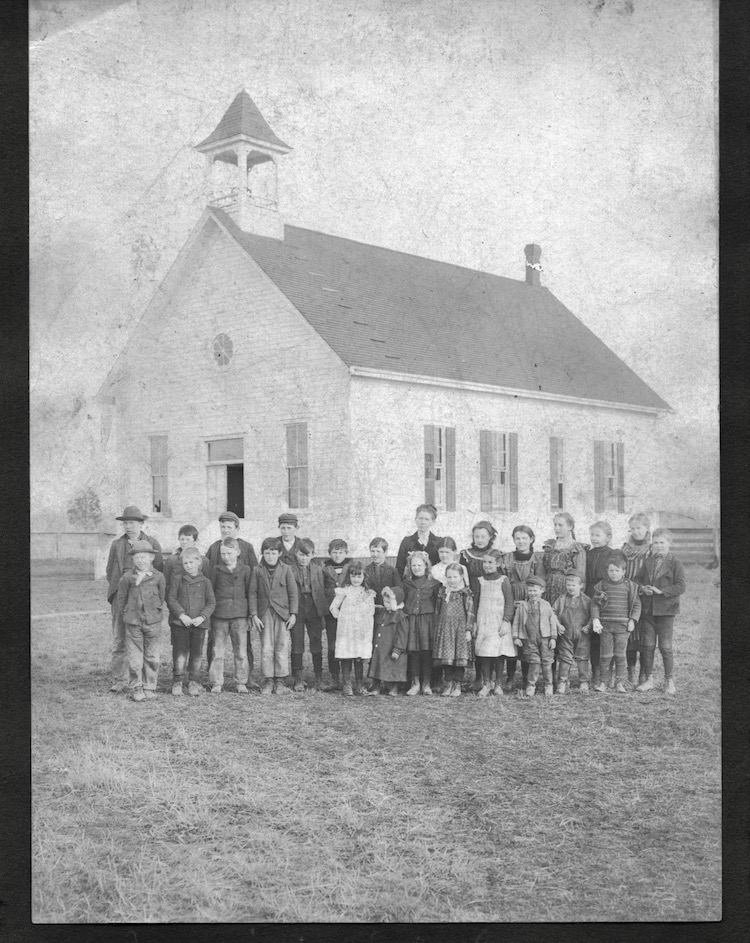

But there’s so much more. Bruce asks me to move a green scale holding down some books and files, and he retrieves a bill of sale for $10,205.84 for items his grandfather purchased as the high bidder at a sheriff’s sale in May 1930. There’s his parents’ Mount Vernon marriage license from 1924. Here’s the $1,000 insurance policy that the bank had in a box containing the wills of David and Margaret McCormick. And of course, there are the photographs. Photos of grandparents, parents, aunts and uncles, La Conner High School football and track teams dating back more than 100 years ago, the 1903 class from the Jenning’s School at Peth Corner that includes Charles and George McCormick and their siblings (somewhere Bruce is sure he has an original ink well from the school). There is even a picture of Bruce from 1939 looking like the Skagit Valley answer to Huck Finn.

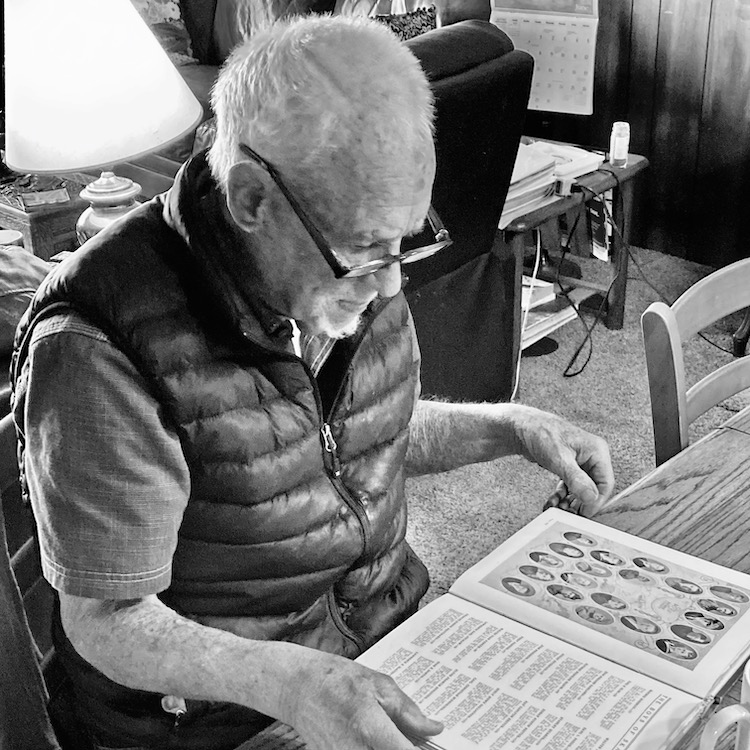

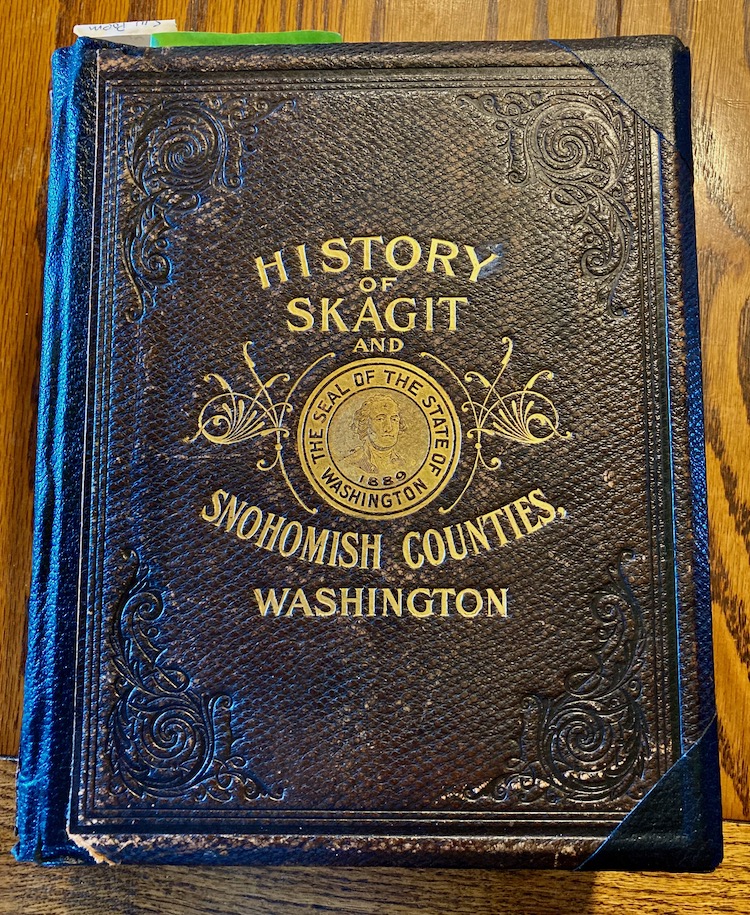

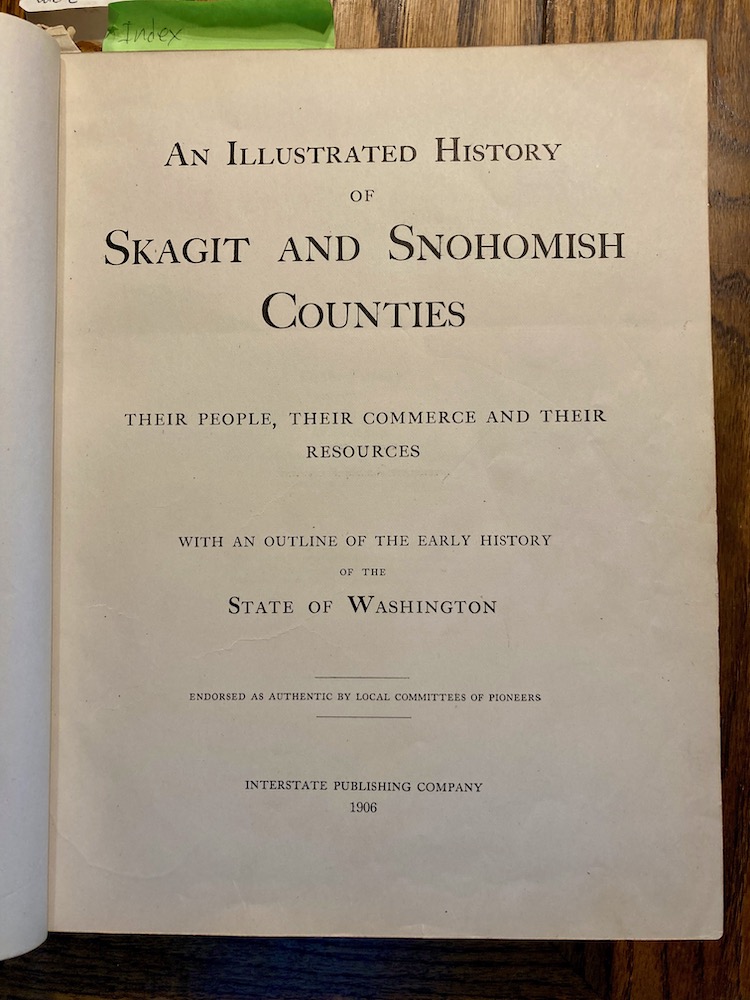

Looking through all this, and listening to Bruce, you’d better believe that “Tales From the Magic Skagit” story ideas were going off like a chain reaction. But the absolute piece de resistance — the crown jewel — was to be found in a massive tooled leather book that Bruce set down in front of me. At first glance it looked like a family bible from the 19th century — one that contained not only the Old and New Testaments with engraved illustrations, but also the family history of births, marriages, deaths, and other notable life passages.

What I read on the cover of this book, however, was (in gold embossed letters) “History of Skagit and Snohomish Counties, Washington”. In the center of these words was the seal of the State of Washington — 1889. Opening the book to its title page revealed its subject matter as, “An Illustrated History of Skagit and Snohomish Counties — Their People, Their Commerce and Their Resources”. Further examination revealed that it was published in 1906 by the Interstate Publishing Company and “endorsed as authentic by local committees of pioneers.” In terms of “Tales From the Magic Skagit” source material, I felt like John Sutter at a certain mill race on the American River in California in 1848. It was a Eureka moment. “There aren’t many other copies of this that I know of,” Bruce told me as he watched my eyes widen. What is particularly amazing about this tome is that it is a virtual who’s who of original pioneer families, complete with biographies that include — you guessed it — David McCormick. Suffice it to say that if you come from a 19th century immigrant family who settled in the Skagit Valley, you can read all about them in Bruce’s book.

Which, no surprise, is precisely what I plan on doing in the months (most likely years) ahead, Lord willin’ and the crick don’t rise. I’ve talked to Bruce about doing a series of future “Tales From the Magic Skagit” stories based on both his recollected and collected histories — and that’s why I wanted to take the time to introduce the man to you. We’ll be hearing a lot more from him, or at least thanks to him, in future “Tales From the Magic Skagit” episodes.

Of course, when one speaks of future stories with Bruce, it is well to keep in mind that the man will soon be turning over a third digit in his odometer — but I’d put better than even money on his making it at least that far. He does have some good genes for longevity (“My mother’s side goes up to 106,” he tells me). I’m looking forward to sharing Bruce’s stories with you, and I’m especially looking forward to some of the personal connections you may have with the people and places they feature. I think you’re going to enjoy these glimpses into our Magic Skagit history, as reflected in the life and times of “Honker” McCormick.