Tales of the Magic Skagit: Treaty Time

Part 3 of Swedebs Park Tells the Swinomish Journey

For thousands of years, our people existed as hunters and gatherers. We got our food and materials from land and water, moving from place to place in harmony with the seasons. We harvested fin fish, shellfish, and marine mammals from the Salish Sea and the rivers that fed it. We caught birds with nets attached to long vertical poles. We hunted deer and elk, drying the meat for winter months, utilizing the bones for tools and hides for robes. We picked berries and dug camas bulbs and bracken fern roots. In the autumn, we took care of the land by burning the prairies to keep them open for the berries and roots, and as growing areas for the game we hunted.

— from an informational display at Swedeb’s Park

The women were employed in making mats & large baskets for holding their provisions…In one place we saw them at work on a kind of coarse blanket made of double twisted woolen yarn & curiously wove by their fingers with great patience & ingenuity into various figures. The wool for making these blankets…is very fine & of a snowy whiteness, some conjectured that it might be from the dogs of which the Natives kept a great number.

— Archibald Menzies, The Vancouver Expedition (1792)The first contact between the Swinomish people and Europeans occurred in 1790, with the unintended consequence that many native communities were decimated by new and deadly diseases against which they lacked any immunity. Barely a decade following Lewis & Clark’s journey from St. Louis to the mouth of the Columbia, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) established forts in western Washington, introducing a new era of trade. Swinomish would travel great distances to Fort Nisqually and Fort Langley in British Columbia to trade at the HBC posts. Among the most immediate differences these interactions made in the lives of the Swinomish people was the introduction of the potato, which they planted and harvested in patches near their winter villages. They were also introduced to Catholic missionaries, who were less interested in trade than in the acquisition of souls for Christ — and far more profound changes lay ahead.

Then the Pioneer Came

Here are some thousands of acres of flats…When tide is full it looks as if it was all cut up into Islands & you could pass with canoes or larger craft all about it for miles…the grass is fine & the world here is full of wild geese, ducks & other fowls. The Indians drive sticks close together all through the cuts & when the water goes out get any amount of fish, especially salmon.

—Jared Fox's Memorandum, 1853It was long before the Swinomish Flats began to settle up with any degree of rapidity. At high tide the Indians paddled their canoes wherever they wished…The marsh was ramified by countless sloughs, big and little, many of them long since overfilled and cultivated over. In the summer tulle, cattail and coarse salt grass flourished and it was the home of many thousands of wild fowl and musk rats, an ideal hunting ground for the Indians.

— An Illustrated History of Skagit and Snohomish Counties, 190625 years ago the water rose (sic) twice a day and covered the Swinomish flats: then the pioneer came with his spade and shovel and laid the foundations for future prosperity.

— Northwest Magazine, 1897It was the fundamental relationship with the land more than trade goods and missionaries that defined the growing cultural divide between the First People and the New People over the ensuing decades following first contact. As one of the Swedebs Park displays states, with considerable restraint, “Our way was to live with the land and care for it, but not to ‘work it’ the way traders, missionaries, and the white government thought we should. With the coming of white men, our ancient relationship to land and water changed abruptly. The newcomers curtailed our traditional pursuits — our fishing, hunting, and gathering.”

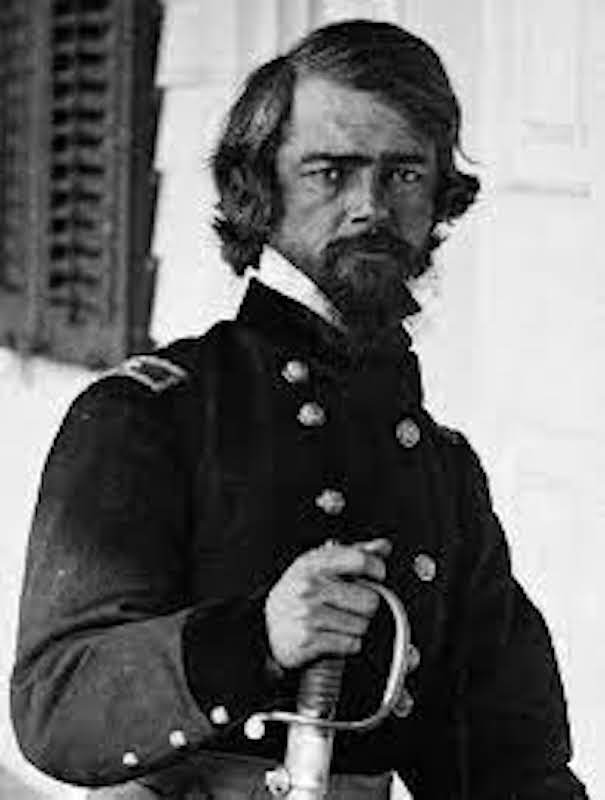

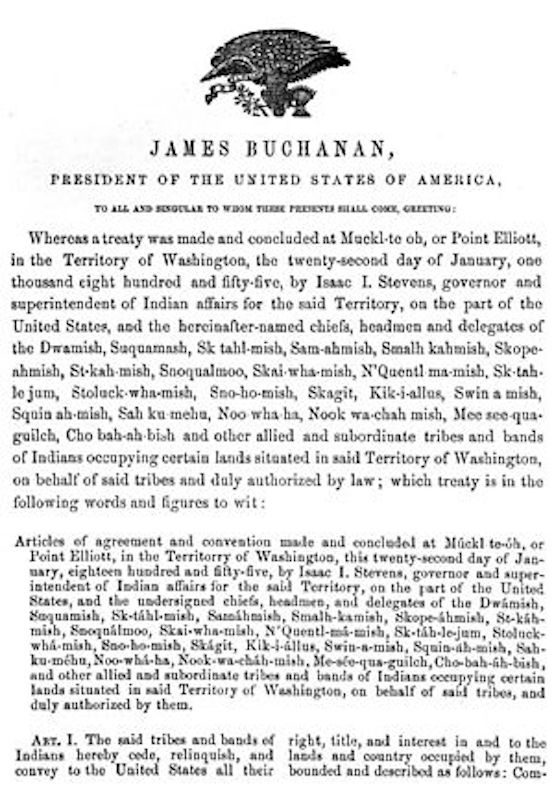

In 1855, a number of Pacific Northwest tribes and bands, including the Swinomish, Lower Skagit, Kikiallus, and aboriginal Samish signed the Point Elliott Treaty at Mukilteo, Washington (negotiated by the state’s first territorial governor, Isaac Stevens). In the wake of the treaty, settlers from the east began “reclaiming land,” building an extensive system of dikes and ditches on the floodplains, estuaries, and tidelands east of the reservation — an area that supported some of the richest salmon habitat in the world — and dramatically changing the ecosystem that supported the Swinomish people.

In 1863, settlers’ claims were staked at March Point at the northern end of the Swinomish Reservation, despite complaints to the government. In 1873, President Ulysses S. Grant simply removed March Point from the Reservation territory. By 1879, just 24 years after Treaty Time, over 10,000 acres had been diked for conversion to agricultural lands, a process that accelerated through the 1900s.

Article 5 of the Point Elliott Treaty had specified, “The right of taking fish at usual understood and accustomed grounds and stations is further secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the territory, and of erecting temporary houses for the purpose of curing, together with the privilege of hunting and gathering roots and berries on open and unclaimed lands.” Nevertheless, these guarantees rang hollow in the face of a continuing land grab. It would take decades to begin fulfilling treaty promises, including payment to the Swinomish for surrendered lands.

As one of the Swedebs Park informational displays laments, “The newcomers curtailed our traditional pursuits — our fishing, hunting, and gathering. They did this in spite of our having specifically reserved these rights in the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott. We wanted to continue following the way of our ancestors. But the new restrictions challenged the very essence of who we were as the First People of this land.”

The Destruction of a Culture

In the decades after Treaty Time, the newcomers’ government pressed us to become farmers so that we would assimilate into their society: from the 1860s through the 1920s, the federal agent assigned to oversee our reservation was officially titled the ‘Farmer-in-charge.’ A succession of these agents tried to force us away from our traditional lifestyle, from our dependence on the sea, the rivers, forest and prairies. However, their way was not to be. We understood the mechanics of cultivating food, but our way of caring for our people and encouraging a continual supply of provisions differed fundamentally from the government’s goal of turning us into farmers.

— from an informational display at Swedeb’s ParkA truer interpretation of the Point Elliott Treaty’s intent can be ascertained in the words of Michael Simmons, the government appointed “Indian Agent” with the Tulalip Agency, who in 1860 noted, “The peninsula (on) Perry’s (Fidalgo) Island is also reserved. There it is intended to establish the Skagget, Kikealans, Swinamish, and other bands. Upon this . . . I would erect some necessary buildings for the accommodation of white employees, provide work cattle and tools, and proceed to open farms, making the Indians in all instances perform the labor under the supervision of white men.”

In addition to depriving them of their traditional means of sustenance, Indian Agent Simmons’ assessment of the desired relationship between the Swinomish and white settlers points to another assault on the existence of the Swinomish. The attempt by the government to transform a people whose way of life was based primarily on hunting and gathering into European-style cultivators was doomed from the start by the land they were expected to farm. “The land on the Tulalip, Madison and Swinomish (reservations) is of such a poor quality that it affords but little encouragement to the Indians to follow farming as a business!,” is how Indian Agent John 0’Keane (Tulalip Agency, 1879) described the situation.

Twenty-three years after Agent O’Keane’s observation, another Indian Agent, D.C. Govan, offered the following insight: “The Indians, as a rule, are not systematic farmers … Many of them, especially the old Indians, depend almost entirely on the never-failing food supply of Puget Sound. With their beautifully fashioned canoes and necessary nets for fishing, they are armed and equipped for the battle of life. They care little for land, and it is only desirable as a refuge when the stormy and inclement weather forces them to forego their favorite pursuit of fishing. In the berry season they gather large quantities, which are dried and canned for winter use!”

By the turn of the century, the role of Indian Agent had been redefined by the Orwellian title, “Farmer-in-Charge.” The man bearing that title in 1902, Edward Bristol, cogently observed, “There has been but very little progress in agriculture (here) during the past year. The Indian does not like farming, and a large portion of the reservation is not adapted to farming. The soil on the upland is very hard and gravelly!”

Souls for Christ

The influence exerted on the Indian people by the schools is marked and incalculably great. After the church, the school is the great civilizing element here. Those who have been brought up in the school now form a considerable element of the population, and as they have abandoned all the Indian habits and customs, in a lesser or greater degree, they form a separate class from the old Indians.

— Alfred Marion, Indian Agent, Tulalip Indian Agency, 1878. As much of a failure as converting the Swinomish into farmers proved to be, especially when forced to cultivate poor soils, greater cultural damage was done by an entity that should have followed a higher law: the Christian Church. Father Casimir Chirouse, a Catholic missionary, began the first school for Point Elliott Treaty tribes at Tulalip in 1857. As one of the informational displays at Swedebs Park relates, “The longhouse of our ancestral village, Txiwúc, once stood where you now stand. In time, this place became the central hub of life on the Swinomish Reservation. St. Paul’s Catholic Church Mission began here in 1868, and the Swinomish Day School was built just south of the church in 1897. Our children attended classes here through the third grad, after which they were sent to Tulalip Boarding School, over 50 miles away. There, far from their homes, they were forbidden to practice familiar ways or even to speak Lushootseed, their own language. The gulf between our traditional teachings and these government schools was as painful as the separation between parent and child. Both left lasting scars on our community.”

In the years after the treaty, the Swinomish adapted to new ways of living while struggling against great odds to retain their culture and traditional teachings. Many people moved to the reservations and continued living on the sea for sustenance. Others went to work on neighboring farms, in logging camps, or in the canneries of Anacortes. Some stayed where their families had lived for generations, such as at Penn Cove or Whidbey Island, or moved to towns and cities in the Puget Sound region.

Despite the closure of the boarding school in 1932, the deep cultural and familial wounds in the Swinomish Community that were inflicted by the Indian Schools remain. If this legacy of pain were the final chapter in the Swinomish Journey, its story would forevermore be a human tragedy. In the coming decades of the 20th century, however, changes would take place within the Swinomish Tribal Community itself that would not only begin healing the wounds of Treaty Time, but would proudly proclaim to everyone in the Skagit Valley, First People and New People alike, that the People of the Salmon remain, and that their way of life is both restorable and relevant in ways that have the potential to heal us all.

But that’s the subject for the final segment of this series, borrowed from one of the Swedeb Park’s displays, “A New Spirit of Hope.”