Heartbreak, Betrayal, and Poetry: The Legend of Lynden, Washington

One of my favorite movies of all time is “Legends of the Fall.” As cinematic experiences go, it delivers on pretty much all the themes that make a Hollywood classic: doomed romance, family estrangement and reconciliation, tragedy and benediction — all of which are set against a sweeping background of big skies and big mountains. And, of course, it has Brad Pitt, which means that my wife is more than happy to watch it with me whenever I feel like revisiting the epic. As a confirmed Westerner, no small part of the movie’s appeal is the landscape I’ve come to associate with my years of traveling through the high lonesome country of Idaho and Montana.

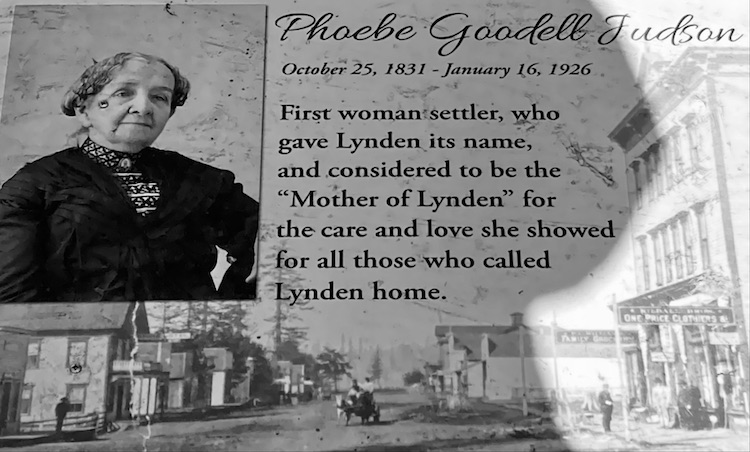

I think it was my love of “Legends of the Fall” that resonated with me when I first beheld the statue of a diminutive matron in Victorian dress in downtown Lynden, Washington. A nearby sign with a photograph that may have served as the model for the statue identified the woman as “Phoebe Goodell Judson (October 25, 1831 – January 16, 1926). First woman settler, who gave Lynden its name, and considered to be the “Mother of Lynden” for the care and love she showed for all those who called Lynden home.”

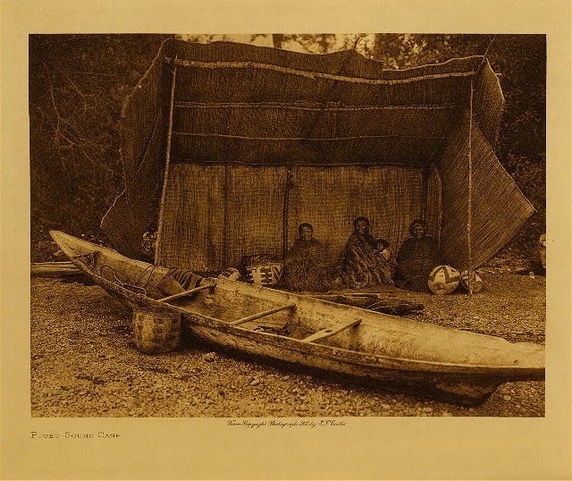

The reference to Phoebe Judson as the “Mother of Lynden,” while true from the standpoint of the immigrant wave of the late 19th century, overshadows an earlier origin story — that of the Nooksack tribe, whose history goes back thousands of years. According to Native tradition, the Nooksack people have occupied the watershed of the Nooksack River — from the high mountain area surrounding Mt. Baker to the salt water at Bellingham Bay and extending into Canada north of Lynden and in the Sumas area — since the beginning of human existence on that land. There is nothing in Nooksack tradition that speaks of ever living anywhere else. Studies in linguistics and archaeology indicate a stable population of speakers of Salish languages, with no migration into the Georgia Straits/Puget Sound region, for the past several thousand years.

This was the land and its original settlers that Colonel James Patterson encountered when he came to the Fraser River in the 1850s in search of gold. His search proved fruitless, but he settled at the site of present day Lynden in the early 1860s and built a cabin on the north side of the Nooksack River, near the site of the Nooksack Indian village of Squahalish. It was here that he met “Lizzie,” an “Indian Princess” of the “Nooksacht” tribe. They married and raised two daughters who they named Dollie and Nellie.

Their relationship was the stuff of Hollywood drama. Left alone for long periods while Col. Patterson was away on business, and treated like a slave upon his return, Lizzie eventually ran off with a handsome young hired hand of the Fraser Valley tribe, leaving her daughters behind. Col. Patterson apparently found the responsibilities of being a single dad onerous. A friend, one Captain Roeder, introduced him to Holden and Phoebe Judson of Olympia, to whom, after some discussion, Col. Patterson offered a curious proposal: in return for taking responsibility for raising his daughters, he would hand over his Nooksack riverside homestead.

Thus it was that in 1870 the Judsons found what Phoebe would describe in her pioneer-era recollections as their “ideal home.” Along with the Coupe homestead to the west, and the Haley Family’s settling to the east — and with “many Indian friends such as Chief Jim Yelokanim, Sally, Joe, and others” — a new settlement evolved. Incorporated in 1891, the city of Lynden was born. It was given its name by Phoebe, who was inspired by a martial poem by Thomas Campbell that was set in a riverside town called “Hohenlinden.” In an apparent fit of romanticism, Phoebe changed the “i” in the arboreal reference to a “y” because it “looked prettier” that way.

Phoebe Goodell Judson passed away on January 16, 1926 at the venerable age of 95. The town she named endures, and strolling the streets of downtown Lynden, population 12,000 (making it the second largest city in Whatcom County after Bellingham), one would be forgiven for thinking that the town’s origins were Dutch. In actuality, Dutch immigration into the area was a demographic phenomenon of the mid-20th century, and was responsible for the prevalence of dairy farms. The town’s population has nearly doubled during the current century, with Dutch accounting for the predominate ethnic ancestry.

The native inhabitants of Lynden endure as well, despite their post-first contact vicissitudes. According to the tribe’s official website, “Research has identified 25 traditional winter village sites, although no more than maybe 15 of these were occupied at any one time, even before the severe population decline of the historic period caused by the new diseases. Most of these villages were in four clusters along the Nooksack River between modern Lynden and the mouth of the South Fork above Deming. The people used a broad area for hunting, fishing, gathering of foods, and traveling to visit other groups.”

The Nooksack Tribe’s website estimates its population from 250 years ago as likely numbering about 1,200 – 1,500 people. Surprisingly, there are today about 2,000 enrolled tribal members. Sadly, unlike other tribal signatories to the Point Elliot Treaty of 1855, in which title to the land of much of western Washington was exchanged for recognition of fishing, hunting and gathering rights and a guarantee of certain government services (if you count forced removal of native children to schools that further stripped them of their cultural origins as a “service”), Lizzie Patterson’s people were not granted a reservation — and were therefor not recognized as a Tribe by the Bureaus of Indian Affairs.

But that’s the subject of another story. Like “Legends of the Fall,” it’s one that entails a lot of heartbreak, but that hopefully ends with a sense of absolution and hope.