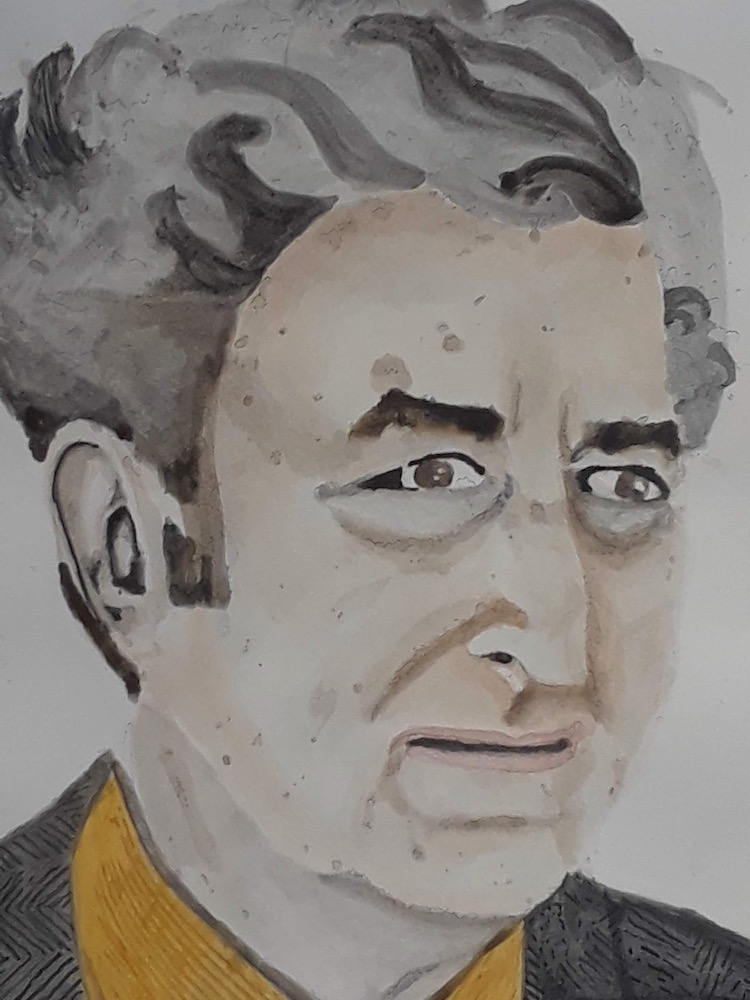

Tales From the Magic Skagit: The Legacy of Henry Klein, “Town Architect”

“From the beginning — I was the first architect in our county — I saw myself as the ‘general practitioner’ who heals the visual wounds we inflict on ourselves, and in the process hopefully finds himself.” — Henry Klein

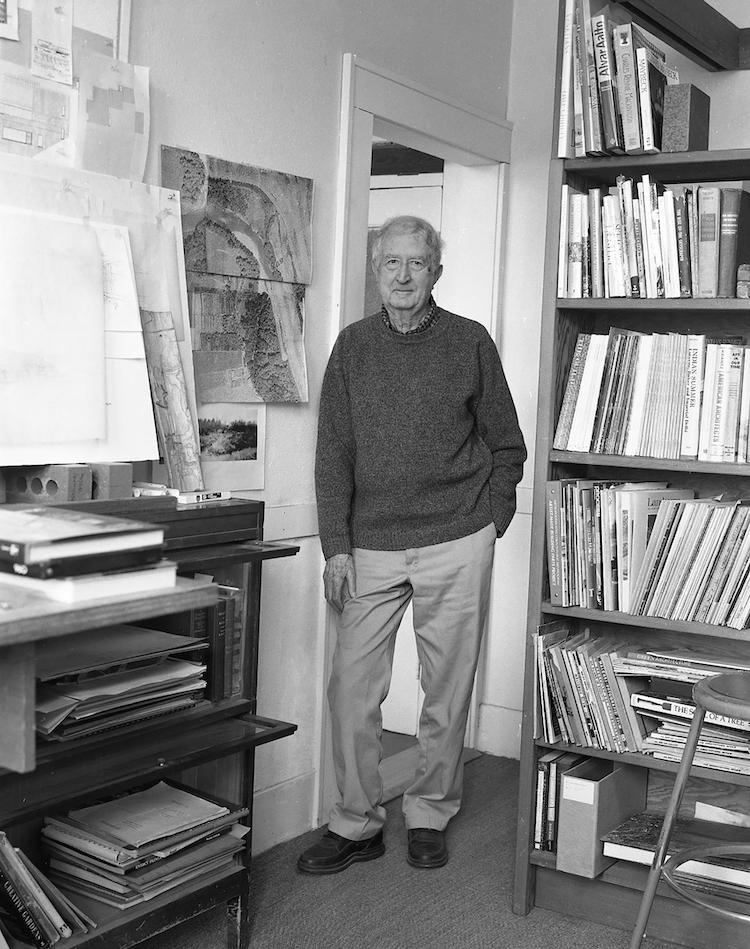

The last exhibit featured by the Skagit County Historical Museum in 2020 — before The Great Pandemic put an end to public gatherings — was on the legacy of Henry Klein, the German-born immigrant who founded the first full-service architectural firm in Skagit County, and whose vision defined a design esthetic that has come to be uniquely associated with the Pacific Northwest, even while its “general practitioner” was to become more modestly hailed as “the town architect.”

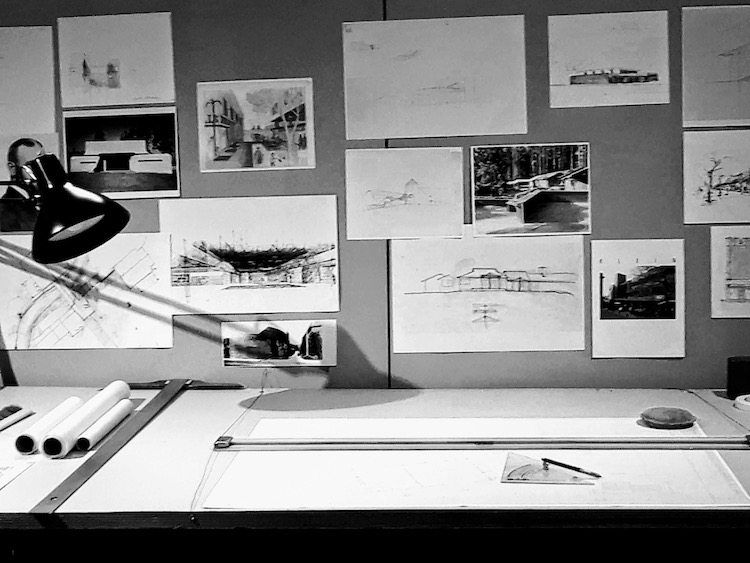

An acknowledgment is in order before I go any further. The following story about the life and work of Henry Klein would not have been possible without the substantial creative effort put into the exhibit by the firm Henry founded in the middle of the 20th Century, HKP Architects, and the commitment of the Skagit County Historical Museum in providing the exhibit venue. This displays, consisting of photos, quotes, drawings, models, and biographical details of Henry’s career, also chronicle the evolution of HKP, and are the primary sources from which I’ve drawn for this story.

Equally significant in its telling, however, has been the willingness of HKP Architects partners Brian Poppe and Julie Blazek in sharing their memories of Henry and the significance of his work in shaping how we see ourselves as Skagitonians and Pacific Northwesterners through the most visible manifestations of that identity: the homes and buildings that we live and work in. Meyer Sign extends its profound thanks for their consent to be interviewed, and for their firm’s many contributions to our community beyond enabling last year’s impressive museum exhibit.

Having moved to Mount Vernon from Boise, Idaho in 2013, it didn’t take me long to realize that there was something about the Skagit Valley that attracted artists — a gravitational pull that had less to do with its proximity to Seattle than with the quality of its light and the color and textures of landscapes sculpted by rivers, islands, cultivated fields, forests, and glacier capped mountains. From the standpoint of visual awe, the Magic Skagit has always punched above its weight.

Henry Klein and his wife Phyllis felt that attraction with their very first visit to the Skagit Valley in the early 1950s, while on vacation from Henry’s internship at the architectural firm of Pietro Belluschi in Portland, Oregon. But while there was already a resident community of artists who were dedicating their careers to conveying the Magic Skagit experience through a variety of media, there was as yet no one who had taken up the challenge and opportunity of expressing it through architectural design. Henry Klein forever changed that.

Henry Klein was born in 1920 in Cham, Germany — a picturesque town that holds the distinction of being a provincial capital in Bavaria. He began his education in Switzerland before transferring to Cornell University, where he received his Bachelor’s of Architecture in 1943. Although I have yet to come across an explanation of what beckoned Henry to America, given what was happening in his country of origin between the time of his birth and graduation from Cornell, one can only speculate.

Henry worked in a number of New York architectural offices before moving heading West to Portland, Oregon in 1948 and taking a job in the office of local architect Pietro Belluschi, who Henry was to cite as a mentor in shaping his design approach. There’s no doubt that Henry was talented enough to leave his mark on the Portland architectural scene, but the fact that barely four years after arriving in Oregon Henry and Phyllis decamped to the rural splendors of Mount Vernon (population: 6,000), where Henry became the first practicing architect in Skagit County, speaks loudly to the attraction this place exerted on him. HKP Architects partner Brian Poppe offers the following explanation: “Growing up in Bavaria, I think that the small town charm and the rural nature of Mount Vernon spoke to him.” Co-partner Julie Blazak concurs, “The landscape was also a factor.”

HKP Architects began with all the modesty of Henry’s own personal and professional demeanor. As Brian Poppe recalls, “The firm was started in 1952, and the legend is that Henry started it in the closed back porch of someone else’s house, about a block south of the Mount Vernon library. He felt he needed to be downtown, so he found somebody who would essentially let him camp out at their home. Two years later he ended up in an office space on the second floor of the Matheson Building — which is where it remained until we moved it over to the old post office building in 2018.” (Henry had passed away five years earlier).

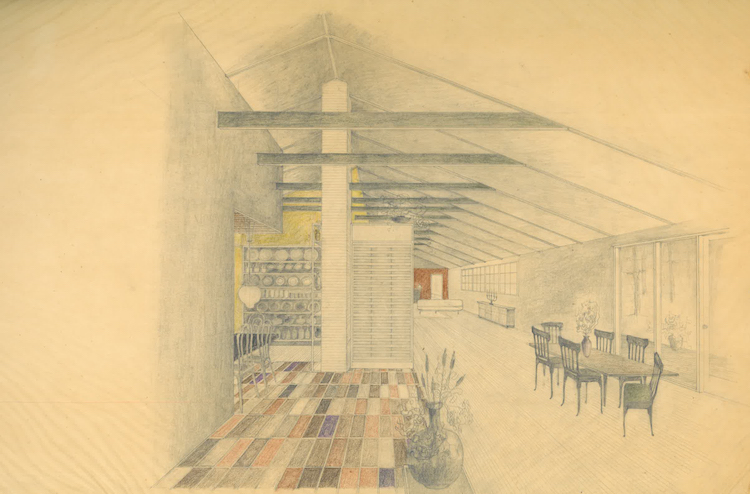

Henry’s first commission in Skagit County was known as The Brotherton House, built for the man who founded the Bozeman Pea Cannery in Bozeman, Montana and went on to found Pictsweet, Inc., a food freezing establishment. Even with this first home design, elements of Henry Klein’s design esthetic began to emerge. Characteristic design details include the Dutch gable roof form, a generous entry/porch, open rafter daylighting at overhangs, exposed collar ties and signature masonry fireplaces that also served as space dividing elements. The Brotherton House was submitted to the American Institute of Architecture (AIA) Design Awards following its completion, and the Skagit County Historical Museum exhibit included the original awards submittal board.

The commonly cited architectural influences on Henry are his fellow northwest architect Paul Thiry (hailed as the father of architectural modernism in the Pacific Northwest), the Finnish architect Alvar Aalto (this was, after all, the era of the Danish Modern esthetic), and his former employer and mentor, Pietro Belluschi — but Henry also defied a prevailing stereotype of his craft in the post-war period. Says Poppe, “In the ‘50s there was an image of a successful architect as one who took a site by its throat and forced it to their will, like Howard Roark (the fictional architect of Ayn Rand fame). Henry was 180 degrees from that image. He was a gentle and humble person who let the client and the site speak to him to find that connection.”

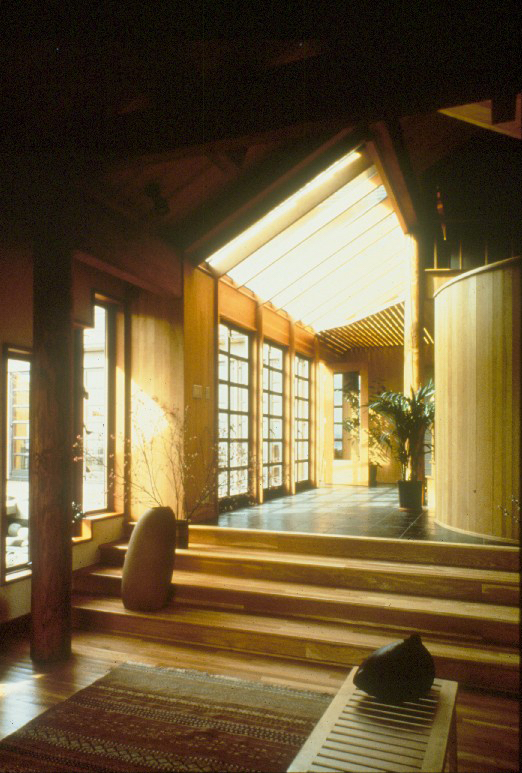

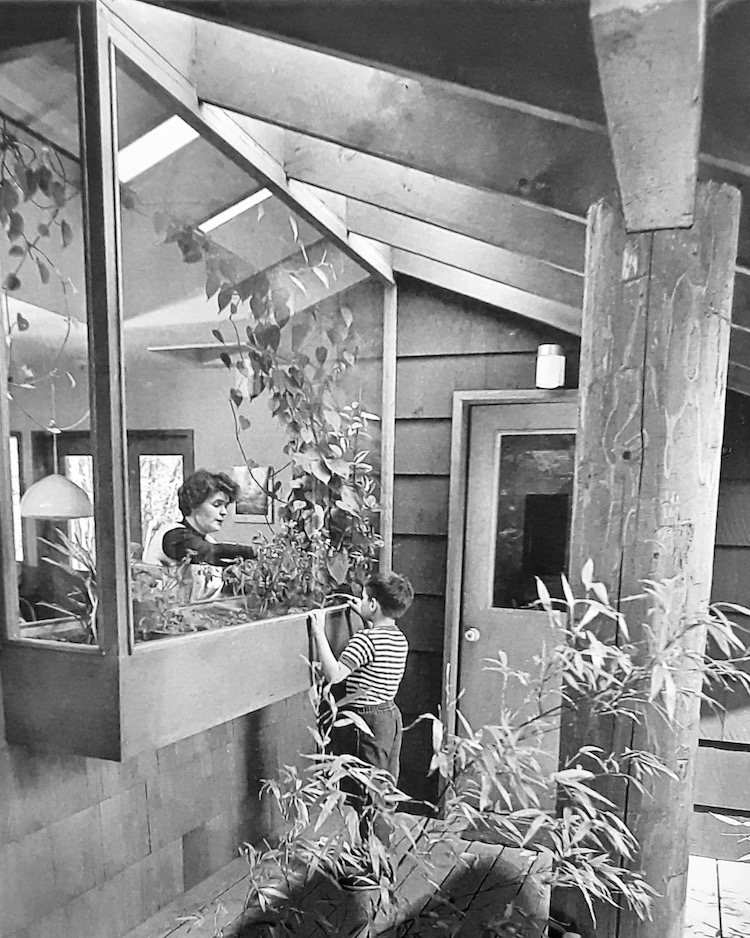

Henry’s homes made wonderful use of “honest, exposed materials” with calming family spaces. But more than anything, what stamped the Henry Klein imprimatur on a building design, whatever its functional attributes, is what Julie Blazek describes as, “The ways he handled site relationships, natural light, the materiality of choices of wood and other materials — and a proportionality to his work that was consistent throughout the years.”

“It wasn’t just that he was adept at understanding a site and how to place buildings to maximize the relationship inside and out,” Julie explains, “but it was the physical connection to the ground and how you entered the site. Was it on grade? Was it elevated? All these subtle considerations that he made to connect you to the site to make those spaces much more special besides filling a function. That’s an aspect that often gets overlooked — how he was able to work with light and rhythm and patterns. Those things flow through all the work that he did.”

The Henry Klein exhibit at the Skagit County Historical Museum did an admirable job of walking visitors through the evolution of the architect’s style and its imprint on the Skagit Valley and surrounding communities, organically arranging exhibit items in decade-based clusters. Taken together, they clearly outlined the trajectory of Henry’s career.

During the ‘60s, Henry’s office grew in size and stature as bigger projects and commissions came its way. More expressive interior structure, sometimes even with stylized roof trusses, were highlighted. Homes featured signature masonry fireplaces and custom designed cabinetry. Local woods such as cedar, douglas fir, and hemlock were featured throughout the house. The designs brought natural light into the home, strategically framing views to the exterior, and brought in natural ventilation to living areas via screened openings. Outdoor social spaces under slanting roofs further blurred the definition between indoors and outdoors. Homes were nestled sensitively within their sites.

The ‘70s saw a continued refinement and “define-ment” of Klein’s design palette: still highlighting natural materials and building forms that seemed to be an extension of the landscape. Large, sheltering simple roof forms provided shelter from the rains, even when outside the home. They also provided shelter from the summer sun for the full-height windows. Often the roofs featured indoor or outdoor skylights that followed the repetitive rhythm of the roof structure, exposing and expressing its structural elements of the roof.

HKP houses continued to be designed around the persons that would inhabit them, becoming an extension of and a framework for their lives. Signature fireplaces were a continuing theme, while building massing and volumes continued to be broken either by stepped roof lines or “hinge points” separating uses — or sometimes separating a parents’ bedroom from those of their children.

Henry even collaborated with artists and philanthropists to design what would today be referred to as “tiny homes,” but were then conceived as potential second homes (think mid-century modern cabins) and low-income housing. The 402 square foot unit shell could be built for $4,000, while a finished three-bedroom unit was estimated at just under $11,000. Fully furnished with works of art from the collaborating artists brought the cost to $12,000 — an amount that today would handily purchase a used vehicle that might sadly end up sheltering a homeless family.

Homes increased in size as the firm headed into the ‘80s, but the attention to scale and proportion were cleverly dealt with by compartmentalizing some spaces into wings or clusters, or creating themes of linear organization. Even with the addition of second floors, overall building design forms typically laid low to the land and were extensions to the surrounding landscape. Signature elements still prevailed, including light brought in at the ridgeline and the extensions of roof rafters. Fireplaces continued as organization elements, and there was, as always, Henry Klein’s enduring honesty and expression of materials.

In its consideration of Henry Klein’s legacy, the HKP exhibit offered the following summary:

“Over the years, he designed award winning, regionally recognizable public and private projects of all size and scale. He retired officially in 2004, after overseeing more than 600 projects. The residential work he produced remains some of the finest architectural expressions of Northwest architecture. Among his many honors are the 1981 Louis Sullivan Award and the 1995 AIA Seattle Chapter Medal.”

“Throughout fifty years, Henry built his practice surrounded by “Associates” and “Partners”. And while he maintained an influence on the designs springing forth from the office, he also mentored and developed those around him to positively impact their communities with designs based in beauty, sensitivity to context, and an expression of northwest materiality.”

For Brian Poppe and Julie Blazek, the legacy of Henry Klein is deeply felt in both their professional and personal lives. In describing what set his mentor apart from other architects — and human beings — Brian goes back to the oft applied adjectives, ‘quiet and humble’.“

“Back when Henry interned for Belluschi in Portland, the mental image I have of Pietro was that he had a mezzanine that overlooked the drafting floor with all the other dutiful workers. I never felt that sort of hierarchy in working with Henry. It was much more a sense of collaboration, and in very few instances would he come right out and tell you to do something. He’d rather have a conversation about finding the ‘right way’ and understanding why something was important and how to address it.”

“One of the qualities I most appreciated about Henry was his appreciation of knowledge,” Poppe adds. “He was constantly learning, mentoring, and encouraging my own learning and development. Even though I knew he had the answers to my questions, often his first response was ‘what do you think?’ — and then we built from there.”

Julie Blazek remembers Henry’s “generosity.” “I was really green when I worked with him — I came in (to the firm) pretty late. He never treated me like I couldn’t do things, and he gave me space to explore. We had amazing conversations about very nuanced things in architectural design.”

Years after his death in 2013, Julie finds her appreciation for her former boss and mentor undiminished. “He became what used to be called ‘the town architect.’ People respected him and valued his input, no matter whether it was a house, a shed, or a public library. We have his drawings of spice cabinets — he could do anything. That spoke volumes to me when I came here and found out more about him. He was so about good design, and how that impacts us in so many ways in our lives. His story and his values are what brought all the rest of us to this firm.”

Henry Klein’s legacy certainly lives on in the culture and aspirations of the firm he started in a friend’s back porch at the mid-point of the 20th Century. Leaning into that legacy, Brian Poppe notes, isn’t about “blindly copying his designs, but more about the why and how of what he did.”

Brian cites Henry’s fundamental appreciation of how underlying design elements are connected to a site as an element of his legacy that his firm carries on. “Henry understood by being on the site where the sun was going to have the most impact, where the predominant winds and striking views would be, and how and when to anchor to the site, stand apart from it, or integrate into it,” says Brian. “It may seem obvious, but he understood that even though it rains here a lot, people still want a connection with outside — so a lot of his designs had these sheltered outdoor rooms that connected with the indoors so you could still engage with the outdoors safely and have the benefits of both environments.”

Poppe also put his finger on how Henry Klein’s design esthetic was intertwined with the little rural community he chose to dedicate his life to. “The interplay between interior and exterior spaces give you a rich architectural palette, especially in terms of depth of view. You don’t have that in an urban setting. Here your depth of view is only limited by the landscape, not by other structures.”

Brian and Julie cite a number of HKP Architects’ projects that they believe would have made their mentor proud. These include the Swinomish Dental Clinic, which Brian describes as “speaking to those values of natural use of materials and connectedness to the site” that Henry’s work exemplified. Julie points to the recent addition to the Orcas Island Library — “a storied and much loved community building in Eastsound” where, she says. “we were tasked with adding on and doubling the size of the library. We wanted to honor and respect the existing building by creating something that didn’t copy it, but that extended and complimented it as a community hub for so many people.”

The values of commitment to community are yet another attribute of the Henry Klein legacy that permeates the company he founded. “It is perhaps more in our values and in our commitment to our community and who we want to have as team members. When you are aligned in your values and goals, the architecture is a natural outpouring of that commitment — a higher calling to do good work and be good stewards of this area and be engaged in it.”

From my visit to the Henry Klein exhibit at the Historical Museum, I found that the most eloquent assessment of Henry Klein’s legacy and its resonance in our lives as Skagitonians came from Henry Klein himself — and I’ll let the man have the last word in this episode of “Tales From the Magic Skagit.”

“Lacking great patrons, I decided early to elevate my clients to that station. I tell them that their commissions are important and that they can make a difference even though to them their building may seem unimportant in a larger scheme.”

“My practice increased, not because its results were seen as art, but because the earnestness of my purpose was perceived as honesty; the trust it brought me gave me renewed courage to impress on my new patrons my strong belief that their building entailed a larger responsibility than to oneself; that no matter how small, the architectural statement carried beyond their property lines, to their neighbors, our town, our region and perhaps even beyond.”

Beyond indeed, Henry. Thank you for helping us see ourselves more clearly through the architecture you’ve bequeathed, and the design esthetic and the values that inform it…and that continue with the enterprise you founded more than half a century ago.