Tales From the Magic Skagit: Valley of Our Spirits

I like to reflect the emotion, the movement of life, the power of witnessing what I see and imagine. What I remember as I reflect on a memory or imagined event. Life has color, weight, power.

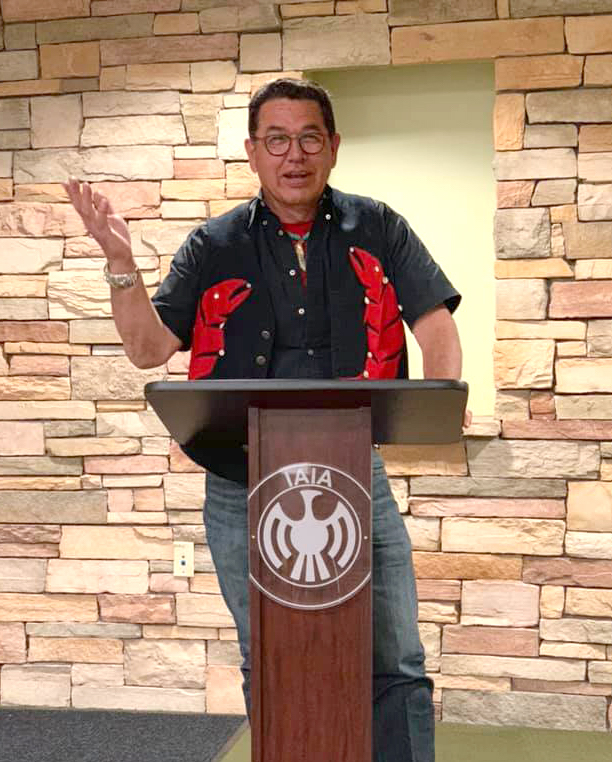

– Jay Bowen, Upper Skagit artist

The inspiration for the 20-foot metal sculpture that rises compellingly over the plaza of Mount Vernon’s Riverwalk, at the west end of Gates Street, is one that goes back 170 years. Its origin story was bequeathed to its designer, artist and Upper Skagit tribal member Jay Bowen, by his great-great-grandfather. The story continues as part of an oral tradition that is at the heart of the totem pole that he and two fellow artists created for the Mount Vernon Arts Commission, known as Valley of Our Spirits.

This is the story, as Bowen related it to me.

One evening, back in the mid-1800s, two explorers who were venturing up the Skagit River stepped out of the night and into a ceremonial circle of my great-great-grandfather’s community. It was the first encounter between what my family subsequently referred to as ‘the New People’ and those of the Upper Skagit who had been part of this landscape for thousands of years.

The story told by my family is that my great-great-grandfather signaled for the men to sit down, and they were given a place of honor in the ceremonial circle. At a pause in the ceremony, my great-great-grandfather put his staff in the ground and asked both men to come over and pull it up.

Now, these were two young, strong men who had just hiked 75 miles into the wilderness. They tried repeatedly to lift the staff out of the ground but were unable. My great-great-grandfather went over and gently pulled the staff from the ground. He then put it back in the ground and flung it to one side so that it was swaying back and forth. He motioned for the men to come over and stop the staff from moving. Both came over to try, and both were thrown to the ground. My great-great-grandfather reached out and stopped the staff’s motion, and again pulled it out of the ground. That was the first moment of the meeting of cultures.

Given my Judeo-Christian upbringing, I have to admit that on hearing this story from Bowen I was immediately reminded of another tale of magic and mystery that involved not only a staff, but also an encounter between peoples of different cultures: the story of Moses in the court of Pharaoh. However apocryphal it might seem to us as 21st century “New People,” the story’s meaning for Jay’s ancestors is as fraught with allegory as the Exodus Tale of Old Testament fame.

“What my great-great-grandfather was trying to explain to the ‘New People’ was that we have a very complex and powerful culture that we are willing to share, if you are willing to share it with us. This is the story that has been passed down through my family. I love the term “New People” because it is one that you can’t make a derogatory statement about. Growing up in the Valley, I’ve heard every derogatory term you can imagine and more about each successive generation of emerging cultures. If the term ‘new people’ could just work its way into our language, it would change the way we perceive each other.”

Which is the point that Jay’s totem pole design makes with all the visual drama of his great-great-grandfather’s staff and the rod of Moses.

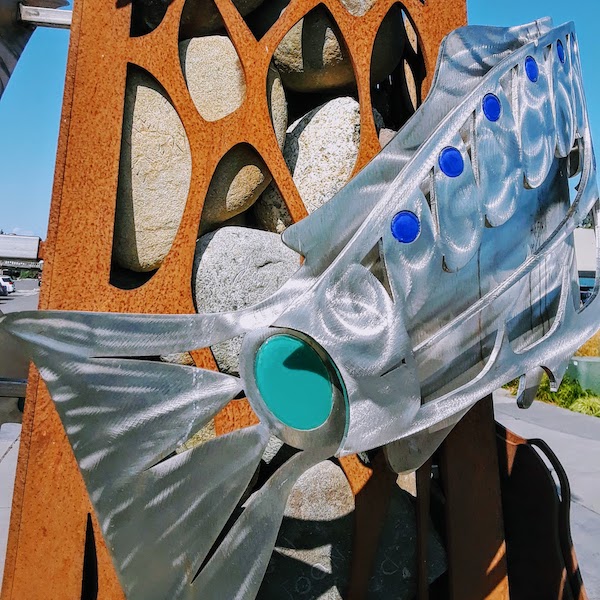

“A totem is an infinite library to express what you want to say,” Jay said in an interview with the Skagit Valley Herald at the time of Valley of Our Spirits’ dedication. “All the salmon — king, silver and sockeye — and the otters, ravens and bear represent the animals of the Valley. Their job is to represent every living creature in the Valley. The eagle on top represents God (FYI, its beak is covered in 30 sheets of 24-carat gold leaf). On both sides of its wings there is a hand, one of which represents the New People, and one that represents the Native People.”

Bowen wryly observes, “I never designated which hand is which…on purpose. That would be the beginning of a fight.”

“The sculpture itself is meant to be looking down into the water. The rocks in it, the river’s bottom, are all from the Skagit River — and on the rocks are names of people from all over the Valley and the United States. New People, native leaders, old families. All those names are there for healing and remembrance. That is designed so that 150 years from now, when restorative work is being done on the sculpture, each one of those names could be the basis of a genealogy that would show the diversity of who we are — so there are all sorts of people involved, not just native names.”

“Healing and remembrance” are dominant themes of Bowen’s totem pole design, just as they are of his life as an artist and an indigenous American. “I was mentored in the responsibility of God-given gifts,” Bowen states on his website. “Raised in the Skagit Valley Washington, I got my higher education at Western Washington University, Institute of American Indian Arts, and Rhode Island School of Design. I have practiced my art and raised four children while making custom fine jewelry and other mediums. To date, my art includes poetry, steel sculpture, glass blowing, fine gold jewelry and oil paintings.”

“I like to connect to the spiritual world and my walk as an intimate experience. My paintings are healing and are all meant to be medicine. My sculptures are healing and uniting humanity in a common goal of understanding and concerns for each other’s lives. My poetry speaks of the human experience unspoken. I use the power, color and movement to express the life around us. I have learned to live in two worlds and find common ties. I refer to myself as an artist…and define myself as an Expressionist.”

The propelling vision for Valley of Our Spirits began with a large piece of steel in the backyard of local metal sculptor Milo White. White saw more than just a hunk of metal. He saw the beginnings of a Native American-inspired totem pole — but recognized that he lacked the cultural knowledge to realize his vision. It was at this point that he reached out to Jay Bowen.

Bowen worked on the design of the totem pole over the next two years. “The city of La Conner was originally going to buy it, but their city council backed out,” he recalls. “And then Mount Vernon wanted to buy it, but they didn’t think we would actually be able to produce it. After about six to eight months we decided to do it for the cost of material, just as a matter of principle, and because we wanted the message to be out there.”

As it turns out, the message resonated with the Mount Vernon Arts Commission. One of the Commission members at the time was Cathy Stevens, who reached out to me through the Meyer Sign Facebook page after seeing our initial post of a totem pole photo along with an appeal to learn something of its history (a big Meyer Sign shout out to Facebook follower Rogan Milnor for putting us in touch with Jay Bowen) .

“I was the committee chairperson,” Stevens wrote us. “We obtained some of the funding from several years of grants from the Mount Vernon Tourism fund. We initially investigated the structural considerations of an above ground water feature on the (Riverwalk) plaza. We eventually changed the theme of our competition to a ‘Water Inspired Public Art Feature,’ and our RFQ called for an artwork that would be conceptually rich, thought provoking, accessible to the general public, maintainable, and safe.”

Bowen’s and White’s vision eventually encompassed a local glass artist and frequent collaborator of White’s, Lin McJunkin. It was McJunkin who created the colorful and intricate cast glass inserts that were incorporated into White’s CNC-cut metal designs. Together, the three artists’ contributions imbue the totem pole what McJunkin describes as “an intentional feel of movement.” Bowen credits White with the totem pole’s sense of dynamism (as an aside, the sculpture lights up dramatically at night).

“Milo is a metal genius,” says Bowen. “He understands metal beautifully. He took my sketches and transposed them onto the computer, and then sent them off to be cut and bent. He had to figure out all the math for the curves. As you go up with the fish there are different curves, and he never lost sight of what the vision was. The curves express our language, and it is flexible. It is a 100-percent native sculpture in a contemporary interpretation. I needed it to speak to the New People in a way that they could relate to.”

The three artists’ contributions extend to the 300 rocks encased in the totem pole’s structure, all of which were gathered from the Skagit River and are engraved with the names of people important to the artists.

After more than three years of artistic endeavor, Valley of Our Spirits was dedicated on a rainy March day in 2019. When I asked Cathy Stevens if the result of the Mount Vernon Arts Commission RFQ met the organization’s expectations. She graciously replied, “I feel that the Water-Inspired Feature chosen by the selection panel of the Commission couldn’t be a better representation of our shared community with Salish history. The artists outdid themselves in a visually stunning piece of water-inspired art.”

We at Meyer Sign & Advertising would concur with Cathy Stevens’ assessment.

In their own way, each of the artists responsible who brought Valley of Our Spirits into being sees the object of their creative vision as more than just a striking piece of public art, and each continues to visit their creation with a sense of fulfillment. “The energy it adds to this place is amazing,” White was quoted as saying in the Skagit Valley Herald story about the totem pole’s dedication. “I still love it — it has not lost any luster to me.”

In that same article, McJunkin spoke of visiting the work since its dedication, and engaging with those who gather to admire it. “A lot of times I watch and wait and then go talk to them,” she said. “It’s an opportunity to open a dialogue in our communities. I can see it being a gathering place…a focal point.”McJunkin’s observation is heartily endorsed by Bowen, although he is more inclined to use the word “medicine” in defining their creation’s appeal. “It’s a working piece of medicine,” he says. “If you’re having a bad day, come down here and stand by it.”

As a member of the Upper Skagit, Valley of Our Spirits carries an additional resonance for its designer. “The sculpture is about the history of the people, about how we put God at the forefront of everything, and the spirit helpers and the spirit world is a daily aspect of the native community from morning to night, and it obviously translates because people can identify with the sculpture even if they can’t understand it,” says Bowen.

“People think that the story of the Skagit Valley began around 1850. The stories of my people began between 20,000 and 40,000 years ago when we first came to the Valley. But it is also a tribute to the progression of people through the Skagit Valley. There are indigenous peoples from Alaska who migrated through here on their way to New Mexico to become the Navaho People, and our tribe hosted them along the way, sharing technology and stories and all sorts of other things.”

“People have come and gone from this valley for thousands of years. We don’t own it…we’re just here for awhile.”